By Nelson Santana and Emmanuel Espinal

July 19, 2025

Leer en español: José Cestero: El alma expresionista de la plástica dominicana

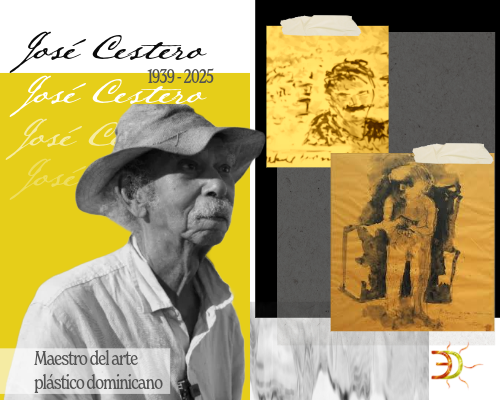

Dominican painting bids farewell to one of its most emblematic figures. The renowned José Cestero, a pioneer of modern national art and a fundamental reference of expressionism in the Dominican Republic, passed away on Wednesday, July 16, at the age of 88 in his home in the Zona Colonial. His passing marks not only the departure of an exceptional creator but also the end of an era in which art served as a form of resistance, memory, and celebration.

Over more than six uninterrupted decades of creation, his artistic legacy extends far beyond the canvas, deeply connecting with the cultural, political, and urban development of the nation. Cestero acted as a visual observer and chronicler of a country in constant evolution, turning his work into a kind of shared personal logbook.

From the Zona Colonial to the World

Born in Santo Domingo on March 19, 1937, José Cestero was part of a generation that came of age under the Trujillo dictatorship but found in art a language of freedom. He showed an early inclination toward drawing, and his formal training began at the National School of Fine Arts, where he studied under giants like Joseph Fulop, Gilberto Hernández Ortega, and José Gausachs.

After graduating in 1954, he moved to New York, where he came into contact with modern currents of expressionism and abstraction—key influences that would shape his lifelong style. But it was upon returning to the Dominican Republic that his artistic voice solidified into one of the most disruptive and perceptive in the country.

Art and Liberation: The Militant Artist

In 1960, following the fall of the dictatorship, Cestero returned to the country and joined the collective Arte y Liberación, alongside figures such as Silvano Lora, Ada Balcácer, José Ramírez Conde, and Iván Tovar. This avant-garde group sought not just aesthetic renewal but also a break from the conservative values of cultural officialdom.

Arte y Liberación showcased an art practice committed to marginalized sectors, history, urban life, and the periphery. Cestero became a kind of visual chronicler of the chaos and beauty of Dominican everyday life. Through portraits, street scenes, and spiritual reflections, his work captured what many preferred to ignore.

The Unmistakable Stroke of Yellow

His style is defined by an expressionist language with a strong emotional charge. The color yellow, omnipresent in his work, was not a random choice. In a 2022 interview with Diario Libre during a retrospective, the artist explained:

“The color yellow is a symbol of madness, of clinical pathology. That’s what yellow is. That’s where Van Gogh’s work and that of many great Impressionist painters in old Europe come from.”

Cestero’s stroke—intense, rough, vibrant—seems to emerge straight from the subconscious. His human figures are distorted yet full of humanity. His painting carries the urgency of someone aware that time is limited, yet the perseverance of someone who refuses to forget.

A Monumental Body of Work

Throughout his career, Cestero participated in over 100 exhibitions—both solo and group—in the Dominican Republic, Europe, and Latin America. The José Cestero Museum highlights that his works are “in personal collections and public and private institutions around the world.”

He represented the country in high-profile events such as the Italo-Latin American Graphic Art Biennial in Rome (1979), the International Painting Festival of Cagnes-sur-Mer in France (1985), and the São Paulo Biennial in Brazil (1989).

Locally, he left an indelible mark on the Museum of Modern Art, the Eduardo León Jimenes Art Contest, and the National Biennials of Visual Arts, winning awards and mentions for works such as Estudio de niño con juguete (Study of a Child with Toy) (1964) and Juan Calalú, apaga la vela y prende la luz (Juan Calalú, Blow Out the Candle and Turn on the Light) (1990).

Dominican Macondo and Tributes

In 2023, he participated in the exhibit Macondo in Santo Domingo, offering his personal interpretation of Gabriel García Márquez’s work through his Caribbean lens. According to Diario Libre:

“José painted Gabo in his town of Aracataca writing the book with a pencil. Always ‘playful’, he confessed that for him, his Macondo was Canca la Rana, on the banks of the Ozama River, where he swam and fished as a boy.”

His creativity—infused with humor and sensitivity—constantly reflected his surrounding reality. The urban, the personal, the social, and the fantastic coexisted harmoniously in his artistic cosmos.

Recognition and Controversy

In 2015, he received the Premio Nacional de Artes Plásticas (National Visual Arts Award), the highest recognition granted by the Dominican State. He also earned accolades in various editions of the Eduardo León Jimenes Contests and other important biennials.

In early 2025, a video showing him moving with difficulty through the Colonial Zone caused public concern. Many believed the virtuoso was in a state of neglect. However, his friend Rolando Leclerc clarified:

“The maestro has people who care for him. He is a very special person with a lifestyle that he leads his own way.”

Cestero preferred to always wear his blue shirt, shorts, and sandals: “It’s hot, and I like to let my feet breathe,” he used to say.

The José Cestero Museum and His Legacy

During his lifetime, the José Cestero Museum was established in the Zona Colonial to preserve and disseminate his artistic output. The space safeguards a portion of his permanent collection and serves as a venue for new exhibitions and educational programs.

Art critic and Deputy Minister of Culture, Gamal Michelén, described him as “the paradigm of social narrative and one of the most cultured artists in the country.”

Eternity in His Stroke

José Cestero often wandered around carrying a sketchbook—his “eternal companion.” He frequently said that upon his death, he only wished to be remembered in this way.

Today, that wish carries even greater weight. The maestro is gone, but his colors, fragmented strokes, figures, and landscapes continue to speak. Each line holds a story. Each mark reveals a truth.

José Cestero is no longer among us, but his art—like all that is eternal—has triumphed over time.

Related

Family Spices with Cuban Dominican Artist Julisa Mugica

«Especias Familiares» con Julisa Marie Mugica, artista dominico cubana