Contestants at the United Hispanic American Parade / Desfile de la Raza Beauty Pageant, ca. 1970s. Credit: The CUNY Dominican Studies Institute Archives, The Margarita Madera Collection.

By Nelson Santana

October 11, 2017

The annual Hispanic Day Parade is a more complicated affair than detractors would have one believe. Some view the revelers as defenders of Christopher Columbus’ legacy, while many of the participants view themselves as ambassadors of Latin American culture. The polemic is found more in the overwhelming perception that celebrates or highlights Spain and Spanish culture and traditions while simultaneously downplaying the rich heritage of the African and Taíno, Aztec, Inca, Cañari, Tupi, Arawak, and other peoples who inhabited the region known today as Latin America prior to the arrival of Columbus and the slew of Europeans that followed. To partake in any celebration or festivity relating to Columbus is to pay homage to the mass genocide and colonization of the people who inhabited the Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans.

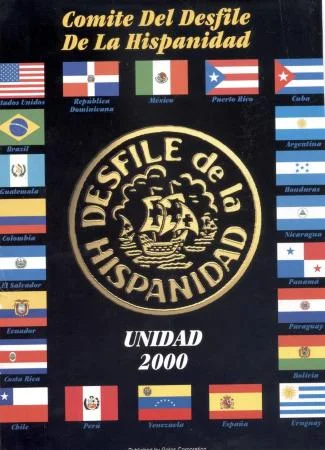

Cover of Desfile de la Hispanidad: Unidad 2000, published by Galos Corporation, 2000. Source: The CUNY Dominican Studies Institute Archives, The Margarita Madera Collection.

This year New York City celebrated the 53rd Annual Hispanic Day Parade on Sunday, October 8. Founded in 1965, the Hispanic celebration started as the Desfile de la Raza (literally Parade of the Races). Some, like the New York Post, argue that the parade itself is a celebration of Columbus. Unlike the Post’s simplistic assertion, the parade is more than a celebration of one detrimental historical figure. The term Hispanic refers more to the Spanish language, which back then served and today continues to serve as the unifying factor among diverse Latin American communities. Spanish allows these communities to re-assert their heritage vis- à-vis Anglo American heritage. It is important to note that prior to the large waves of arrivals of Spanish-speaking Latin Americans in the twentieth-century, many Spaniards made New York their home a century prior in the 1800s, hence the neighborhood of Little Spain in Manhattan. Therefore, when Spanish speakers across Latin America arrived in the metropolis, there already were networks in place established by Spaniards. Rooted within the Desfile de la Raza is the yearning of immigrants to be welcome and accepted in the New York metropole.

“Any affair that praises a vessel of genocide, as in the case of Columbus, in turn commemorates the colonization and mass genocide of a people. ”

Unknown to most people, Dominicans such as the late Álfida Fernández—mother of Hollywood actor Juan Fernández—and Ricardo Rico played a key role in the event’s founding. At the time of the parade’s establishment in the mid-1960s, in New York there were no Dominican Day Parade, Mexican Day Parade, and so forth; Puerto Ricans were the only Latino/Hispanic group that celebrated its heritage via an annual celebration. The sixties saw African Americans and people of Latin American ancestry mobilize to fight for their civil rights. The fifties and sixties, in particular, brought about civil rights changes that turned the United States upside down, forcing the overhaul of the U.S. legal system via new far-reaching laws including the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This cornerstone of civil rights legislation ended segregation in public places and “legally” banned discrimination based on race, skin color, sex, religion, or national origin.

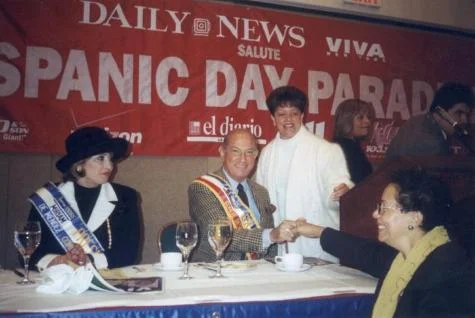

Dominican designer Oscar de la Renta and Margarita Madera. Source: Dominican Studies Institute, New York (N.Y.). The Margarita Madera Collection, ca. 1970-2003. Box 5, Folder 6.

Not Just one Civil Rights

Like African Americans and people of Mexican descent, Dominicans and other Latin American immigrants wanted to carve their own space within the United States. Often neglected in historical inquiries is that between the 1930s and 1950s Mexican-descended people played a crucial role in U.S. labor history. In Civil Rights: Mexican American Workers in Twentieth-Century America (2005), labor historian Zaragosa Vargas places Mexican-descended people—scapegoated by President Herbert Hoover’s administration—at the center of the various U.S. labor movements, thus arguing that workplace discrimination itself served as the major driver of protest for Mexican-descended people. The third Monday of January is a national holiday that honors the life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Similar to Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, and César Chávez, Dr. King, Jr. challenged the systemic system of oppression in which he lived daily and successfully forced societal changes. Current civil rights leaders and activists such as Michelle Alexander, Alicia Garza, George Takei, Colin Kaepernick, and Junot Díaz continue the civil rights struggle in the twenty-first century.

In carving a piece of history and celebrating their culture or “Dominicanness,” Dominicans often are vilified as anti-black or racist. However, dialog should take place to address the history of this festivity. By no means is this a justification to absolve actual racists or those self-loathing Hispanics and Latinos of Native American and African ancestry. But it should be noted that before placing Columbus on a pedestal, a focal point of the parade was and will continue to be to empower Latin Americans by exalting their Latin American roots in New York City and proclaiming estoy aquí para quedarme. Nonetheless, any affair that praises a vessel of genocide, as in the case of Columbus, in turn, commemorates the colonization and mass genocide of a people.

Among those political figures who acknowledge Columbus as a historical figure, a divide is present. Republican presidents Donald Trump and George Bush both overlooked Native Americans in their Columbus Day proclamations, as opposed to presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama who included details about Native Americans in their yearly proclamations. In the United States, several cities have decided to do away with Columbus Day and instead honor Indigenous People’s Day. Of 50 U.S. states, only three have opted to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous People’s Day, with South Dakota the only state to honor both Columbus Day and Indigenous People's Day.

Problem with the Hispanic Day Parade?

Over the years, political correctness appears to have caught up with the parade’s administration. Earlier floats depicted Native Americans as weak or subjugated and African-descended people in shackles. The narrative has shifted with a lesser focus on the glorious conquistador in favor of highlighting more the non-European heritage.

Why did the Hispanic day parade change its name from El Desfile de la Raza to the Hispanic Day parade? When noting the word “raza (race),” did the parade’s founders mean Native American, black, and white, to note this group of people, or was the word “raza” a substitute for nationality such as la raza mexicana or la raza dominicana? The hope is for this article to open a line of inquiry where these and other questions can be addressed.

Margarita Madera and three men on a float. Source: Dominican Studies Institute. CUNY. The Margarita Madera Collection, ca. 1970-2003. Box 4. Folder 12.

Nelson is the producer at ESENDOM and he splits his time between New York and the Dominican Republic. He loves comics as much as he loves bachata and típico. He is currently an assistant professor and collection development librarian. His work has appeared in diverse publications including the first translation project pertinent to the writings of Juan Pablo Duarte. Feel free to hit him up at nelson.santana[at]esendom.com.