Photo:Tess Duran

By Amaury Rodríguez

August 29, 2017

In celebration of #WomenInTranslation month, ESENDOM conducted an email interview with Sophie Maríñez, a poet, translator and French professor at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) in New York City. Maríñez is the author of Mademoiselle de Montpensier: Writings, Chateaux, and Female Self-Construction in Early Modern France (Leiden: Brill, 2017) and co-editor, with Daniel Huttinot, of the first French translation of Haitian-Dominican poet and revolutionary Jacques Viau Renaud’s poetry entitled J’essaie de vous parler de ma patrie forthcoming from Montreal-based independent publisher Mémoire d'encrier.

In this candid interview, Sophie Maríñez offers her thoughts on translation and talks about her upbringing in both France and the Dominican Republic, literature, language, seminal novels by Dominican women in the United States as well as her unending love for both literature and translation.

You’re trilingual. In what order did you learn the languages you know?

I was born in France, of a French mother and a Dominican father who had been sent to Europe by his parents when the U.S. invaded the Dominican Republic in 1965. When Balaguer took power in 1966, all those who were “young and students” were considered communists, and were repressed, tortured, and killed, unless they showed allegiance to the regime or, at the very least, an extremely low profile. Not the case of my father, who was really a communist and had an entry ban on him. So it wasn’t until I was seven that he was allowed back to the country and that we moved to the Dominican Republic. But my parents always spoke to me in French, and I didn’t know any Spanish, so I had to learn from scratch. I was young enough to learn it and speak it without an accent, and yet old enough to preserve my French, since I already knew how to read and write in French. I also loved reading, and most of the books to which I had access were in French, so that helped preserve my mother tongue.

When I was in seventh grade I had my first English class. I was eleven, and all I knew about English were the “música americana” my cousin and I listened to on the radio, singing along in total disparates, you know, not understanding a word of the lyrics but still singing along as if we did? That was my first exposure to English. I had no idea of how cool it would be for me to hear the words “chair” and “professor” and notice how close they were to “chaise” and “professeur.” Woohoo, I thought. This was going to be a picnic in the park.

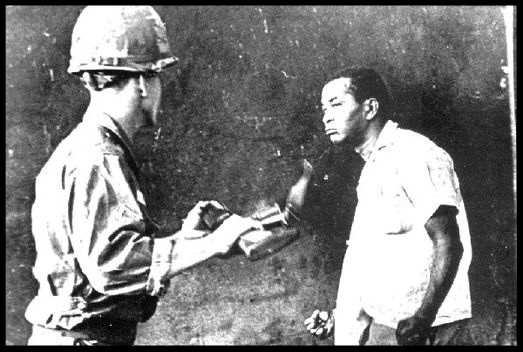

A Dominican man named Jacobo Rincón is seen in this iconic image confronting a U.S marine in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic during the 1965 revolution and second U.S. invasion of the country. Photo: Juan Pérez Terrero

So my ascent into the skies of the English language was pretty rapid and smooth. Soon, I was with the advanced students, and before I knew it, I qualified to be admitted into the Translation program at Universidad Apec, which required advanced knowledge of English. I have to admit that listening to “música americana” continued to be my favorite learning tool, but contrary to my earlier karaoke escapades with my cousin, this time I sought the lyrics that came inside the LPs’ jackets, and translated them for myself so that I would at least know what I was singing along to.

After college, I moved to New York, and decided I loved the way Portuguese sounded. I was working at a translation agency, and needed it to supervise translation projects in Portuguese. So I took some courses at Berlitz and was comforted, again, by how close it was to French and Spanish, and, in a funny way, to Cibaeño Dominican Spanish (lol). I made some Brazilian friends and pretty soon became fluent. Today, my Portuguese is a bit rusty, since I don’t get a chance to practice much, but I don’t believe in such a thing as “forgetting” a language. I have the theory that once you’re in, you’re always in. All your brain does is deactivate the languages you don’t use, which means you can re-activate them when you need them again. It might take a little effort at first, but with some determination, everything comes back.

“I don’t believe in such a thing as “forgetting” a language”

How did you get involved in literary translation?

I think I was a translator ever since I first arrived to the Dominican Republic as a child and had to translate words to myself as a first attempt to understand the new world around me. I keenly felt what is meant by “lost in translation” when I could not find the equivalencies in Spanish for what I wanted to convey in French. And vice-versa. I remember writing a letter to my French grandmother describing my new life in Santo Domingo and telling her about my new pet, a turtle, that “here we call ‘jicotea.’” I think writing letters to my French grandmother was perhaps my first translation act.

Then as a teenager, I was going to acting school, at the National School for Performing Arts, and my mother, a French teacher herself, had a collection of critical works by a famous Hellenist, André Bonnard, who wrote extensively about ancient Greek civilization. I was fascinated by his prose, the way he made the Greeks alive in my mind. I wanted to share that with my classmates at the acting school. So I decided to translate his works into Spanish, all by myself, day by day. It was a good exercise. I didn’t even have a typewriter at the time. But then, life happened, and all the work I had done got lost. It was never published, but I did retain a tremendous respect for scholarly work.

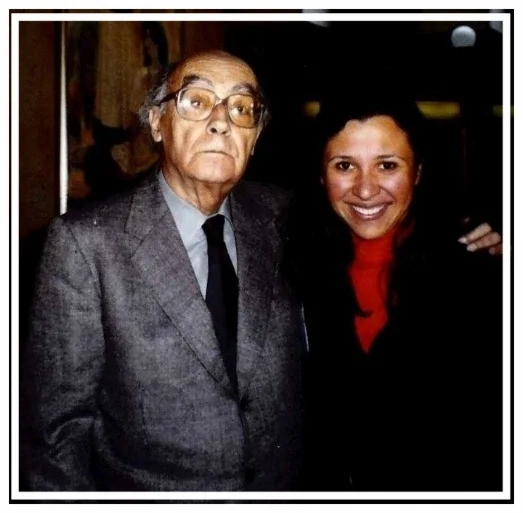

José Saramago and Sophie Maríñez, Mexico City, 1999. Photo: Courtesy of Sophie Maríñez.

Since I was an actress, I had to make the deal with my parents that I was going to at least have a “trade” so that I could support my acting habit. I decided to go for something familiar to me: translation. I already spoke French and was semi-fluent in English, so all I had to do was take both to the next level. Easy! Universidad Apec was offering a new major in French-English-Spanish Translation at the time, and I signed up. I was fortunate to have some really good professors, including Sulamita Puig who taught us about Saussure linguistics, and Minou Tavárez Mirabal, who had just arrived from Cuba. In French, I had Danielle Carron, a veteran French-Spanish translator. For my thesis, I translated the biography of Indira Gandhi, who fascinated me for being the first female president of India.

Soon after graduating, I came to New York, and I was hired at YAR, a leading multicultural advertising and translation agency. I began as a proofreader and editor, but soon became the manager of the Spanish and Portuguese translation department. This first job gave me serious work ethics and acquaintance with what is euphemistically known as a “fast-paced work environment.” I learned the heavy-duty ins and outs of the translation industry, the cost per word and turn-around of a translation project, the quality control process, the clients’ expectations, in sum, all the mechanics of professional translation. Most of the translations we did were technical manuals, but we also did advertising and marketing materials, corporate communications. But then, we were at the dawn of the global era: Internet happened in 1995 and translations began to be outsourced to Argentina, where translators were paid 5 cents/word instead of the 15 cents U.S. translators charged. It was a catastrophe!

“Since I was an actress, I had to make the deal with my parents that I was going to at least have a “trade” so that I could support my acting habit. I decided to go for something familiar to me: translation.”

Literary translation came to me later, around the year 2000, when I was invited to translate Loyda Maritza Pérez’s novel Geographies of Home into Spanish, a translation that, unfortunately, was never published. Then, in 2015, I translated into French Frank Baez’s “La Marilyn Monroe de Santo Domingo,” a poem that speaks of transgenders’ persecution and mistreatment in the Dominican Republic. To me, the poem also speaks of a general state of mind of discrimination and mistreatment of anyone who carries the mark of unaccepted difference—including difference imposed by racial constructs, socio-economic hierarchies, power relations, moralistic judgment, and, of course, sexual orientation and gender norms. So, in this sense, translating “La Marilyn Monroe de Santo Domingo” was continuing the life and extending the reach of this poem, and screaming to the world the heart-breaking iniquity of this injustice.

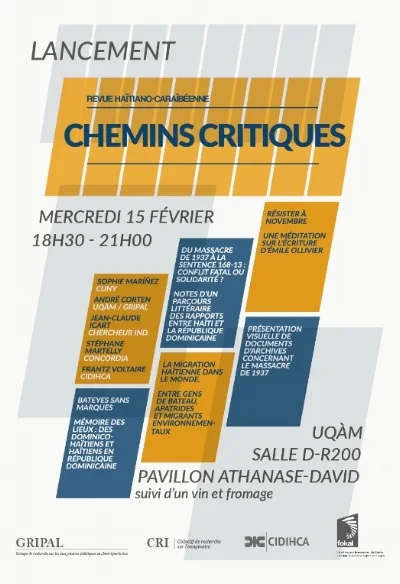

This translation act led me to another one, of similar political reverberations, which is the translation into French of the poem “Two Countries: One Island,” by Julia Alvarez. It was recently published along with the version in Creole by my friend the poet, performer, and visual artist, Michèle Voltaire Marcelin, in the Haitian-Caribbean journal Chemins Critiques. Alvarez’s poem rewrites Pedro Mir’s celebrated “Hay un país en el mundo” to remind us that there are actually two countries in the world, sharing one island and a history of colonization and pain. Alvarez wants these translations to be read at the Border of Lights event that she and other writers, artists, and scholars, including Eddie Paulino, from John Jay College, conduct every year, in October, at the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. This annual event commemorates the victims of the massacre that in 1937 took the lives of tens of thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent.

Announcement for the launch of the Montreal-based Chemins Critiques journal issue featuring a special section on the 1937 massacre. Source: Gripal

Most recently, I was invited to translate and edit the critical translation into French of the poetry of Jacques Viau Renaud, the great Haitian poet who grew up in the Dominican Republic and joined the resistance against the 1965 U.S. occupation. Jacques was hit by a mortar and died a week afterwards, at 23. His contemporaries and subsequent generations agree that he represents the ultimate symbol of solidarity and fraternity between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Because Jacques wrote for his friends and the readers near him, he chose to do so in Spanish, and as a result he is barely known in Haiti. Daniel Huttinot, a Haitian friend and militant living in New York, always had the idea of having his poems translated into French, but it wasn’t until a recent conversation with Amaury Rodríguez that he decided to actually make it happen. Soon, Raj Chetty joined them and they all approached me to coordinate and edit the project, as we were going to do this with a team of translators based in Haiti, Canada, Chile, and New York. Amaury and Raj had already done much scholarly work on Jacques’s life and poetry, and translated his famous poem “Quiero hablaros de mi patria” into English, which they published in the issue on black Dominican studies they edited for The Black Scholar in 2015. Daniel secured the interest of Mémoire d’encrier, the reputed Haitian-Canadian press, as well as the support of the Fokal foundation for free distribution of the book throughout schools in Haiti. The aim of the book, which is titled J’essaie de vous parler de ma patrie and will be published at the end of this year, is to introduce Jacques to Haiti, bring his poems back to his maternal tongue, and put him on the map of Francophone literature. This project has been an incredible honor for me.

“Jacques Viau was hit by a mortar and died a week afterwards, at 23. His contemporaries and subsequent generations agree that he represents the ultimate symbol of solidarity and fraternity between Haiti and the Dominican Republic.”

When did you decide to be a writer and an academic? And which do you prefer: to write poetry or conduct research and teach?

Being a writer has always been a fantasy of mine. As a teenager, I used to keep a journal and write little poems in it. Then, at a more mature stage, reading José Saramago (whom I had the honor to meet and interview later in life) brought this yearning to an excruciating level. I began interviewing Dominican-American writers, and publishing these interviews in a series titled Dominicanos en los Estados Unidos, which appeared in the Dominican newspaper Listín Diario and the now-extinct magazine Rumbo, My immediate goal was to have Dominicans living on the island see that Dominicans in New York were not all drug traffickers—narcotraficantes, tecatos y cadenúses, as they kept calling those of us in the States. Those were the late nineties, and Julia Alvarez had just come out with her novel Yo!, and Junot Díaz had just sprung as a literary sensation with his short story collection, Drown. So, I first interviewed them, and between 1999 and 2001, also interviewed Loyda Maritza Pérez and Nelly Rosario, and wrote a review of Josefina Báez’s Dominicanish. Personally, I wanted to hear from them something that would help me too, as an aspiring writer. However, to be a writer when you are a single parent of two in New York City, as I was at the time, is quite a tall order, and, as in the days in which I was an actress, I had to have a “trade” to support my writing habit.

My “destiny” crystalized when, in 2001, I met my dear friend William Burgos, an English professor at Long Island University. As he heard me speak about all these Dominican writers I had met, he said to me, “Hey, I’m teaching this class on Latino writers, but I think you know more than me about Dominican writers. Why don’t you come and give a talk to my students one of these days?” So, there I was, talking about all these writers, and the students looked at me with these sparks in their eyes, so fascinated. Some of them were Dominican, and they had all these questions and comments. They couldn’t have enough of it. And that’s when I decided that I wanted to do this for the rest of my life. Learn and teach.

So, lucky for me, I found a “trade” whose territory came with unsuspected opportunities for growth and love. And I can’t tell you which of the two—creative writing or academic work—I prefer. It’s like asking me which of my two kids I prefer! They both bring their own sets of blessings and headaches. What I do know is that I need both to keep some sort of balance in my life, and not fall in too much despair when things don’t go my way.

What has been your experience as a writer and scholar?

As a writer, my path has been a bit slow, as I had to deal with parenting, going to graduate school, teaching, doing research, and so on. One of the issues I also have is the competition of languages inside my head. You have no idea how much they interfere with one another. At some point, I will have to address that too.

In the late nineties I received a commission to write children stories for a literacy program in Texas for McGraw-Hill. That was fun. But it wasn’t until much later, upon the passing of Édouard Glissant, who had become a fundamental figure to me as a poet, a philosopher, and a professor when I was at the Graduate Center, that I decided to commit to poetry and write my first poem (in French) in homage to him. Then, I began to participate in poetry readings, enrolled in workshops at the Writers’ Studio in the Village, and was shocked when Small Axe Literary Salon published my poem “Carnival Day in Santo Domingo” in February 2015. Soon afterwards, an academic journal published my Sentencia del Infierno, a series of poems I have been writing in reaction to court ruling 168-13, issued by the Constitutional Court of the Dominican Republic, stripping of tens of thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent of their citizenship.

Ana María Belique, one of the leaders of Reconoci.do at a civil rights protest for Dominicans of Haitian descent fighting for citizenship rights in the Dominican Republic. Photo source: CUSLAR

As a scholar, I have been blessed with the mentoring and support of some of the greatest minds at the Empire State College, where I earned my masters degree in Liberal Studies with a focus on Dominican-American Identity and Literature, and at the Graduate Center, where I completed my doctoral degree in French. At first, I wanted to do my dissertation on the Haitian-Dominican dynamics, but a course I took on 17th-century French women writers took me off that path for the moment, as it made me discover how little things had changed, in terms of misogyny, between then and now, despite many milestones achieved by women over the past century. Still, realizing how despicable Molière had been in regards to women writers of the time was not what took me there, but the fact that women weren’t going to have it and resorted in one way or another to contest misogyny and gendered norms. If they could do it, I though, so could we. And I found tremendous solace in reading their novels, memoirs, letters, plays, and fairy tales for adults, which envisioned alternative modes of dealing with men and marriage. I was glued. And although most of these women writers belonged to aristocratic and noble circles, the way I see it is that female oppression is real and universal. We are not out of the woods yet, and certainly not in places like the Dominican Republic, where abortion is still illegal under all circumstances, including incest, rape, and even the potential death of the mother.

So my first book is coming out this fall under the title of Mademoiselle de Montpensier: Writings, Châteaux, and Female Self-Construction. It is an interdisciplinary study that brings together literary studies with female architectural patronage scholarship to examine the strategies used by women of the period to assert their social and political identities. Although I discuss early women advocate Christine de Pizan and duchess and queen of France, Anne of Brittany, I mostly focus on Mademoiselle de Montpensier, Louis XIV’s first cousin, who wrote novels, memoirs, and a manifesto against marriage. She also built four gorgeous châteaux and other buildings in France, and used them to live out her vision of autonomy and female power.

Now that my first book is out, I’m focusing on the next one, the Haitian-Dominican dynamics project I began at the Graduate Center a long time ago. I’m excited—this is a great time for scholars in the field, as the subject has elicited the interest of a growing, international audience.

Who do you have in mind when you translate a literary text?

Nobody except the text—save, of course, Jacques Viau Renaud. When I translated his poems, I strove to sense what he felt, what he thought, what he yearned for, what he wept for. I could relate to him, as he, too, was seven when he first arrived to the Dominican Republic, did not speak Spanish, and had to adapt.

What challenges do you face as a translator working in the fields of Women, Caribbean, and Dominican studies?

I would say bringing my multiple languages into the same classroom. Academic disciplinary boundaries can be very strict at times, thus continuing this compartmentalization of knowledge by language and “area studies.” Only once did I have the opportunity to bring English, French, and Spanish together. This happened when I was at Vassar, as a visiting faculty in French, and I was asked to teach a seminar in English-French translation. In addition to reviewing seminal works in translation theory and conducting weekly translation workshops, I decided to inflect my Spanish-language side, my Caribbean side, my Dominican side, onto this very white environment, and asked the students to translate different excerpts of Junot Díaz’s The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Now, who does that? It was crazy, I thought, but I didn’t care. So, here we were, reading Junot in a French seminar, and the students had to deal with all his Spanish words and his extensive footnotes on fucú and Columbus, and Balaguer and Trujillo. I almost regretted it because Junot’s style is really difficult to translate and at some point I felt bad for the students who were just learning the techniques. When I come to think of it, perhaps students weren’t so thrilled by the exercise, but I was glad they got to read Junot and experience the different questions a writer or a translator asks himself or herself when going for a word in Spanish, as Junot so often does, leaving the translation task to the reader.

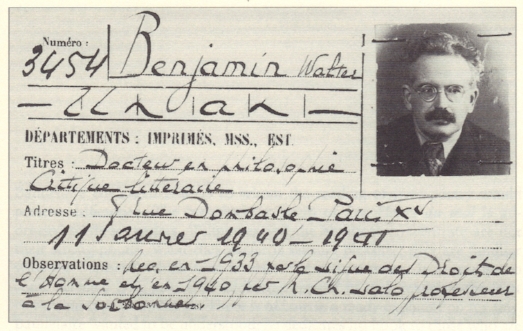

We live in a world where the drums of war are louder than ever before. To echo Walter Benjamin, what is the task of the translator today?

One of Walter Benjamin’s statements on translation that resonate with me is on the importance of conveying the “essential quality” of a literary work—not just the content, but what he calls “the unfathomable, the mysterious, the ‘poetic,’ something that a translator can reproduce only if he is also a poet.” I mention this because contrary to old theories of translation—to which Benjamin subscribes—that establish an antagonistic binary between the original and the translation, making the former superior to the latter, and the latter irremediably and always already imperfect in its aim to convey the entirety of the former (think of the old adage “traduttore, traditore”), I believe there is no such dichotomy.

Walter Benjamin's membership card for the Bibliothèque nationale de France (1940). Photo: Unknown-Bibliothèque nationale de France. Source: Wikipedia.

The original is a gift from the author to the translator, and the translation is likewise another gift, from the translator back to the author, a gift made after having consumed the original, digested its words, its imagery, its rhythm, and arrived to a certain, almost spiritual, empathic understanding of the vision and the aesthetics of the poet. The quality of the translation lies not only in finding le mot juste, the right word, but also in apprehending and conveying the rhythm of the original and breathing in consonance with it. So as the translator consumes the original and produces a translation, both texts become one, eternally attached to one another, irreversibly erasing the boundaries between the eater and the eaten, the self and the other.

So, in this sense I disagree with Benjamin’s statement, later in his essay, that the translation is an “echo” of the original—as if the translator’s role were to remain bodiless, invisible, like Echo, the tragic nymph who was condemned to always repeat the words of her beloved Narcissus, and to never speak her own mind, never be seen, never be recognized, never be loved back. Rather, I see the literary translator's task as one of dialogue with the author, as the translator interprets and remains faithful at the same time, breathing new life into the original text. In this line of thought, the Association of Literary Translators of America has been building awareness for the due recognition of the work of literary translators, urging translators to negotiate with publishers to have their names included on book covers, instead of hidden somewhere in between ISBN and copyright information, as it has so often been done.

For to translate someone’s poem is ultimately an act of love. It cannot be measured or quantified. It defies contracts and transactional agreements. In fact paying a translator cannot even guarantee the quality of the translation. When I translate your poem I do it because I love your poem and I “get it,” nothing less, nothing more. So, in this sense, translation is one of the most intimate forms of writing, as the translator gets very close to someone else’s vision and breath, and, for that moment at least, “shadows” the poet. Still, translation is a creative act in itself, not just the rendering or serving of someone else’s creation. The translation is an offshoot, an offspring of the original, yes, but it is an original too, as it is created by another human, another creator—the translator. In sum, the translation is a work of art in its own right.

“For to translate someone’s poem is ultimately an act of love. It cannot be measured or quantified.”

Translation is also political. Choosing a text for its translation is not an innocent gesture. It implies a statement that this particular text warrants having its life “continued,” as Benjamin would say, or expanded for its readership in other communities. In the Caribbean context, for instance, to translate is to create bridges to reconnect communities that have been divided by the colonial and imperials acts. Thus, to translate is to decolonize. Translating Jacques Viau Renaud, for instance, is a political intervention on the current landscape of anti-Haitian animosity brought forward by right-wing politicians in the Dominican Republic. So when you mention the “drums of war” being loud again, I think of the immense privilege it is to have been handed by life with two, three, or more languages. And since privilege always carries some kind of responsibility, translators have the responsibility of using theirs to help bring people together, to help entire communities speak to one other and heal.

What are some of your favorite translations and why?

My favorite translations are those of José Saramago’s novels by his wife Pilar del Río. Now, if translation is an act of love, as mentioned above, these translations are the act of love par excellence! They make you feel as if the writer himself had done them. Certainly, Saramago was there to help as well, so that made it a true dialogue and recognition of one another’s talents.

What French-speaking writers would you like to translate into Spanish? And vice versa, what Spanish-speaking writers would you like to translate into French?

I would love to translate more Dominican writers into French and more Haitian writers into Spanish, so that we get to know one another a bit more. I think this type of work is long overdue.

____

Related: #WomenInTranslation: Aurora Arias’s Liberation Song

If you like this interview, tell us why at Esendom [at] esendom.com