Photo via The Poetry Foundation

For our new, ongoing Women in Translation Dossier, Esendom interviewed Achy Obejas, a translator, storyteller, novelist and journalist. Achy Obejas is the editor and translator of Havana Noir, an anthology of short stories published in 2007 by independent publisher Akashic Books as well as the author of the novels Days of Awe (2001) and Ruins (2009) and a couple of short-story books including We Came All the Way from Cuba So You Could Dress Like This? (1994) and her latest collection called The Tower of the Antilles (2017). [Her story The Tower of the Antilles appears here]. Obejas is the Director of the MFA in Translation program at Mills College in Oakland, California where she currently lives. Her work deals with Caribbean myths, sexual dissidence, migration, national identity and Cuban society.

In this interview, Achy Obejas talks about her work as a translator, the beauty and irreverence of Caribbean Spanish and some of the challenges facing translators.

Can you talk about your decision to become a translator? Who inspired you?

It was really more of an accident than a decision. I’d always done translations, for my parents and friends, and poetry translations for myself as an exercise, but I didn’t think of myself as a translator. Back in about 2005, I’d become friends with Johnny Temple of Akashic and we were looking for a project to do together. He began sending me Akashic books, which I loved. There was one I was very excited about — Miami Noir. I was then living in Honolulu and was thrilled to finally get it — I’d really hoped to see a lot of Cuban writers in the book. But to my dismay, the representation was not what I’d hoped. There was some crazy time difference between Honolulu and New York but I called him and bitched. To his great credit, he saw my point and then suggested we do Havana Noir.

At the time, neither of us realized it would involve translations. The noir series has tons of translations now but Havana Noir was the first. Because I know so many Cuban writers who always have an English translation at the ready, I just assumed I’d collect these and that’d be that. Of course, I hadn’t read these and hadn’t realized how horrible most of them were. Plus, I wanted some linguistic cohesion in the book. End of story? I ended up translating thirteen of the eighteen stories, each and every one originally written in Spanish. Even then I wasn’t sure I was a translator. But then I had a long talk with David Unger, the kindest man in the world and the head of the translators division at the Guadalajara Book Fair, and he gave me great encouragement. He also recommended me for the Junot Díaz translation of The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

“I’d always done translations, for my parents and friends, and poetry translations for myself as an exercise, but I didn’t think of myself as a translator. ”

What are some of your favorite translations of Cuban literature and Caribbean/Latin American literature in general?

Honestly, I’m not terribly fond of most Caribbean/Cuban literature in translation. Our Spanish is so saucy, so elastic and rich, and I find most translators — especially if they’re not from the Caribbean — kind of freak out when confronted with it and tend to want to tame it rather than surrender to it. The end effect is sort of stiff. That said I thought Andrew Hurley did an amazing job with Reinaldo Arenas, especially The Palace of the White Skunks.

Achy Obejas's translation work has introduced English-speaking readers to the work of both Cuban and Dominican women writing in Spanish.

You translated Junot Diaz’s The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Can you talk about the process of translating it?

It was pretty frustrating. Junot had had a very unpleasant experience with the first translation of Drown, which was rendered into a kind of peninsular Spanish — sort of like translating Toni Morrison into Cockney English. Eduardo del Lago was brought in to rescue the book with a second translation, and he did a fine job but it leaned more toward neutrality and so a lot of the richness of Dominican Spanish was absent. What all this means is that when we started working on Oscar, his first novel, Junot was defensive and already had a lot riding on this translation. He wanted it to sound Caribbean, Dominican. I did too. But though I read Dominican writers and have Dominican friends and am very familiar with Dominican Spanish, I’ve never been to the DR and I’m not Dominican. Cuban’s probably as close as you can get, but still.

The work of Dominican writers Rita Indiana (who writes in Spanish) and Junot Díaz (who writes in English) deal with colonialism, queer life and alternative histories in the Dominican Republic, the Caribbean and the U.S. Translation work by Achy Obejas have made their artistic visions available to a wider public.

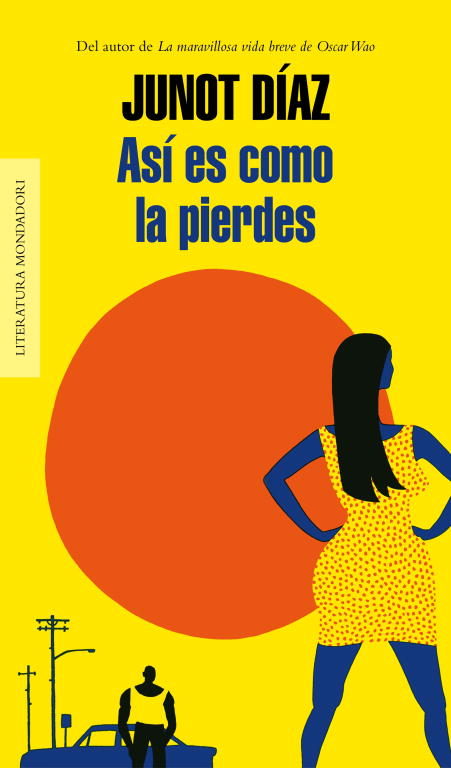

Anyway, Junot had his plan: he wanted to see every chapter as it was finished, and then he’d send it to his sixteen closest friends who’d send me back notes — notes that frequently contradicted each other and which Junot didn’t reconcile. On my end, I hired María Teresa Ortega, one of Cuba’s finest translators, to sort of back me up. And I bought every Dominican slang book I could find and listened to Dominican talk radio every morning while I was doing the translation. I just wanted to hear how people talked and to think about it critically. Toward the end, when there was a full draft, I was lucky that Moira Pujols, the Dominican-born editor of contratiempo, a Chicago-based Spanish language literary magazine, read the whole thing and checked our “Dominicanness.” For This is How You Lose Her, we were on firmer ground — the Spanish translation of Oscar had gotten terrific reviews all over Spain and Latin America and the translation itself was often the subject of much of the reviews. So we cut pretty much everybody out. I did, however, have my friend, the Dominican poet Keiselim Montás read it over, again to check my “Dominicanness.”

What female writers would you like to see translated into English and other languages?

I’d love to see the very fab New York poet Elizabeth Acevedo translated into Spanish, and Legna Rodríguez Iglesias, a young Cuban poet, translated more widely into English.

____

Related:

#WomenInTranslation: Interview with Sophie Maríñez, Poet and Translator

#WomenInTranslation: Aurora Arias’s Liberation Song

If you like this interview, tell us why at Esendom [at] esendom.com